-sigh- I need a raise @steven... alright... -rolls up sleeves-... buckle up, this is gonna be quite long...

There is a lot of "I'm using fancy words here" which make it difficult to understand at first glance, even for myself... As such, there are also replies to posts and replies to those replies whereupon the information in them has been distorted, and as such, overused terminology is conflated with other overused words, leading to further confusion.

As with anything, I would strongly recommend you at least plug your question into google or wikipedia to get a quick synopsis on the subject, and then if any of it is unclear, you can better phrase your questions to fill in the gaps. It also can serve as a bit of a guide on whether you can trust other poster's responses, should they mention similar things to the reference of your choice.

There are 8 billion people on the planet right now... I can 100% guarantee that any question you have, will have been asked at some point in the past... the trick is to find the

right answer.

godlameroso wrote: ↑02 Apr 2022, 18:38

Something you can't analyze, if you get the floor working harder, it means you need less load from the rear wing, which means you can make it lighter because it has to deal with fewer loads. The rear wing is the highest part of the car, and raises COG the most.

The idea of "you need less from xxx" is just not how you go about designing the structure of single components in a system. In this example, if you manage to find more aerodynamic performance from the floor, great... now you have increased your CzS of your whole car, and unless your aero BALANCE is now too far aft (where you would turn down the downforce on the rear wing to move that balance point forwards), you don't need to change the rear wing at all. Weight which is higher off the ground will have a larger contribution to the position of the centre of mass, true - however, having lifted rear wings before, they really aren't actually that heavy. Also, I can tell you from experience that they are made as light as they can be from the get go, because the goal of the overall car design is to still be as light as possible, and then add ballast mass to bring the total up to what the regulation minimum us... and you get to put that where you like (or, you can also deliberately design lower components on the car to achieve the same thing). The stringing of these two differing things together is a little misleading / confusing.

Latios wrote: ↑11 Apr 2022, 17:27

Fluido wrote: ↑01 Apr 2022, 21:18

Latios wrote: ↑01 Apr 2022, 20:54

I mean you need to test. With cores increases, the calculation speed is not increased linearly.

when turbo starts? If both has same turbo ghz doesnt that mean this with more cores is faster?

If really same GHz, more cores may be better, also depends on memory speed. So you'd better test it.

More Cores != More Performance (at least not always)

[just in case; the symbol "!=" means "not"]

I have an entire thread on how CFD is solved at the fundamental level within a PC, whereupon I touch specifically on the correct core to thread to RAM stick ratio... I highly suggest you go read that here:

viewtopic.php?t=28562

Finally, just a note on "turbo"... All turbo means is that if there is sufficient cooling, and it is a "light" workload, the CPU is capable of temporarily boosting the performance of a SINGLE CORE (mostly) to that higher frequency. If your rig does not have sufficient cooling, or your task is highly multi-threaded (where a huge amount more power / voltage is needed) then your "turbo" chip will do nothing more than sit at it's rated speed regardless.

godlameroso wrote: ↑11 Apr 2022, 19:41

The wing is high and when at speed, the aero increases the weight of the rear wing, doesn't it? Perhaps the rear wing affects both COP and COG at speed.

Vanja #66 wrote: ↑11 Apr 2022, 22:57

godlameroso wrote: ↑11 Apr 2022, 19:41

The wing is high and when at speed, the aero increases the weight of the rear wing, doesn't it? Perhaps the rear wing affects both COP and COG at speed.

CoG is a "slang" for CoM, as in mass. Weight as a force depends on mass, but also on acceleration, ie gravity. Since we measure mass by measuring weight, we tend to use them wrongly as synonyms.

In any case, aerodynamic forces don't change the quantity of matter in the car, ie the mass of the car, so they don't change CoG. Engine burning fuel does that.

Vanja basically has it.

CoM = Centre of Mass

CoG = Centre of Gravity

The difference between them is that the centre of mass is the point around which the distribution of all mass in the object is equal, and so if there is a

uniform gravitational field, the object's "Weight Force" (remember, mass and weight are not the same thing!! Weight [N] = Mass [kg] x Gravitational Acceleration [9.80665m/s*2]), then that equal distribution of mass around the object will also be an equal distribution of weight force... meaning that in this specific case of a uniform gravitational field, the CoM and CoG will be the same exact point.

Conversely, if said gravitational field is NOT uniform (think of a black hole spaghettifying you... your toes have a much larger gravitational field around them vs. your head), then even if you had an even distribution of mass around the object, your centre of gravity will no longer be at the same exact point as your centre of mass... because when you use the above formula for a non-constant gravitational acceleration, your weight will change, even if your mass does not.

When you get on a scale, and it displays a number in [kg], what that scale is actually doing is measuring your weight force in Newtons, and then dividing that back through by gravitational acceleration to get a mass in kg that you understand.

This being said... we live on a planet, and gravitational field strength increases as you approach the core, and decreases as you approach the sky. But not by much... The top of mount Everest is around about 99.6% of what you experience on the ground... and so for almost all of our daily activities, it is more than adequate to assume that centre of mass will be in the same exact position as centre of gravity... which has led to the conflation of the terms as being synonymous... which is practically fine, so long as you remember "why" that is.

godlameroso wrote: ↑11 Apr 2022, 23:24

Vanja #66 wrote: ↑11 Apr 2022, 22:57

godlameroso wrote: ↑11 Apr 2022, 19:41

The wing is high and when at speed, the aero increases the weight of the rear wing, doesn't it? Perhaps the rear wing affects both COP and COG at speed.

CoG is a "slang" for CoM, as in mass. Weight as a force depends on mass, but also on acceleration, ie gravity. Since we measure mass by measuring weight, we tend to use them wrongly as synonyms.

In any case, aerodynamic forces don't change the quantity of matter in the car, ie the mass of the car, so they don't change CoG. Engine burning fuel does that.

Aerodynamic forces are the result of the quantity of matter(air) over in and around the car, downforce is measured in Nm, just like the wheel rate.

First off, downforce is measured in Newtons [N], not [N.m] (which would be a torque) -- but this was corrected back in the thread, and I have only included it here for completeness.

Your first sentence isn't strictly true... Aerodynamic forces are made up of several things:

- The normal force (meaning force acting perpendicular to the local surface curvature) on the surface due to the pressure on the surface of the body

- Form drag or pressure drag due to the size and shape of a body

- Skin Friction Drag or Viscous Drag: due to the friction between the fluid and a surface (inside of the object or outside)

- Lift-Induced Drag: the drag generated simply by virtue of the generation of lift

- Wave Drag: caused by the presence of shockwaves and first appears at subsonic speeds when local flow velocities become supersonic (due to the speeding up of the air over the curved aerofoil profile surfaces of a wing)

But there is also stuff like buoyant forces acting on the car, because of the air which the car displaces just by occuping that space, even before it starts moving. You also have a force acting on you right now by all the air that is above your head resting on you because air has a mass to it too.

All of these will have an effect on your centre of pressure, since a pressure is a force exerted over a unit of area, however, when it comes to centre of mass (or gravity), that does not change (** we will come back to this in a second when I reply about "added mass") with aerodynamic pressures acting on a body. Vanja is correct in saying that as the car burns it's fuel, that will change the centre of mass location.

Just_a_fan wrote: ↑11 Apr 2022, 23:57

Downforce does give an apparent increase in weight without the usually required mass increase. Which is why it's so good for going around corners, of course.

I made a post a long time ago about this in the forum which you can find here:

viewtopic.php?p=603780#p603780

However, it seems that my LaTeX scripts have borked themselves... so I've taken a couple of screenshots from one of my uni theses which explained this again, and uploaded them to imgur if you want to follow along. Giving it a quick scan, there doesn't seem to be anything which makes me cringe in my writing style thankfully!!

Zynerji wrote: ↑12 Apr 2022, 00:08

Just_a_fan wrote: ↑11 Apr 2022, 23:54

Nm would be a torque, or a bending moment. Something with a lever arm application.

Isn't a car on wheels a lever with 2 compliant fulcrums?

As just_a_fan pointed out, it doesn't matter what the car's free-body diagram is, since downforce is a force, and a force is measured in Newtons. We tend to think in "discretes" with our daily lives, but the reality is that there is a continuous force distribution profile over every surface of the car. The summation of each component of every infinitessimal space's force vector that points perpendicular to the ground (either upwards or downwards, since we are adding them together), we call downforce if the overall vector still points down. The components that point forwards and aftwards, after summing together, we call drag if the overall vector still points backwards. For an aeroplane, the drag vector remains pointing in the same direction, but the summation of all the up-down vector components leads to a final upwards force, which we call lift.

Where moments do come into play, is that if I have a large downforce pushing on my rear wing, then that force is going to have a "rearward bias" relative to the location of my centre of mass. So if I was to take that downforce and drag force, multiply it by their "moment arm" length relative to the centre of mass location (a fore-aft distance for downforce, and an up-down distance for drag) when I summed that up, I would get a pitching moment (or torque) that would then be reacted by the car's suspension and tyres, lifting up the nose of the car.

The force is Newtons, it's "resultant torques" that it exerts on the car, are Newton-meters.

godlameroso wrote: ↑12 Apr 2022, 16:01

On one side they raise pressure, on the other side they lower pressure. The vanes act like a passive air pump. The low pressure zone behind the vanes acts as a vacuum cleaner for air upstream, accelerating it.

Remember that flow velocity is dependent on the pressure difference between the inlet and throat of a venturi channel. The greater the pressure difference between the inlet and throat the greater the flow velocity. Like an air compressor, the pressure in the air lines is ~6x the pressure at ambient, so the air rushes out of the lines into ambient.

The strakes create high pressure, by the 3rd law, there's an equal but opposite reaction elsewhere.

Turning vanes (or strakes) serve to control the "lateral" element of the airflow that enters or exits the underfloor.

The forward strakes, at least from what I remember, serve to pick up some of the nasty dirty air that is shed from the rotating tyres (which on their own generate six vortices, the middle two of which flip at whim for reasons I can't remember just now) and other upstream aerodynamic components, and outwash it. From there, it can just be pushed out, or it can get sucked up into some of the vortices that the bargeboards and sidepods have managed (think how the Y250 vortex would travel down the length of the car) to "virtually seal off" the underfloor from air rushing from the ambient pressure around it to the low pressure under the car.

The low pressure in the throat and forward part of the diffuser (at the back of the car now) sucks in air from the sides; and because that air also has to funnel in between the rear wheels, there is going to be some amount of messiness introduced. Turning vanes in that region serve to channel that lateral flow and help maintain attached flow in the diffuser - sometimes by initiating "helpful" vortices in that area too.

godlameroso wrote: ↑12 Apr 2022, 16:01

Wings work the same way no? One side raises pressure, and the other side lowers pressure. Mass is displaced and force is generated.

Lift generation is a really complicated topic, because any single answer on it's own doesn't paint the full picture... and it's quite surprising how many mechanisms are at play there...

To the people reading this, let me know below if you'd like to see a write up on "what lift really is" or something...

godlameroso wrote: ↑12 Apr 2022, 16:01

[...]

less airmass means less air pressure. Less air pressure means more acceleration of upstream air, more momentum, means less static pressure(up to a point).

[...]

The strakes are what choke, because that channel is so small, you can see on pressure traces, there's a pressure peak where the innermost strake and the floor interact. That pressure peak indicates sonic choking. From there the only way to further accelerate the air is to lower the backpressure downstream.

[...]

it implies the flow velocity is high enough for compressibility effects to be at play, or that the flow is choked/sonic.

[...]

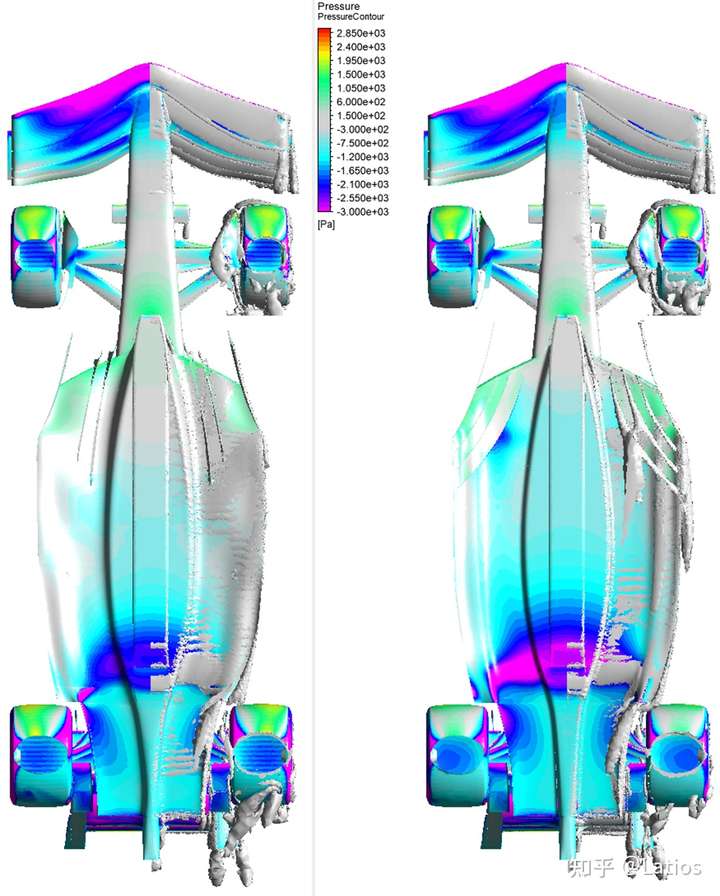

There is no supersonics going on in those pictures and there are no legends or labels or units to tell what range of variables we are looking at is either.

As a reference to people here, air is considered incompressible up to ~0.3 Mach, with the compressibility factor only hitting 10% at around about ~0.7 Mach. There isn't really a certain point at which compressibility effects are at play... they are always there for any amount of motion... we just tend to ignore them for simplicity at low speeds.

Tommy Cookers wrote: ↑12 Apr 2022, 21:50

Fluido wrote: ↑12 Apr 2022, 21:15

godlameroso wrote: ↑12 Apr 2022, 16:53

I imagine aero yaw forces could work to increase or decrease inertia of the vehicle.

You are violate basics physics axioms.

Inertia is the property of mass, not aerodynmic forces.

there are such things as added mass effects

Added mass (at least how I understand it) is the inertia added to a body because the very motion of that body through a fluid when accelerating or deccelerating has to move and/or deflect some amount of the fluid that it is moving through. Inertia is an inherent property of an opbject based on it's spacial dimensions, and therefore it's mass (derived from density). You can't change that number. However, when you do a summation of the required forces needed to overcome that inertia, added mass factors (e.g. buoyancy for instance) will serve to lessen the required applied force to the object to change that object's position / speed / acceleration.

So kind of, but not exactly how it was stated.

godlameroso wrote: ↑12 Apr 2022, 22:02

Ok, so we agree the air has to keep moving, and why does the air have to keep moving? Because if it slows down, static pressure rises. Which means fast moving air is low pressure, why is it low pressure? Because the air spends less time bouncing against the walls and thus exerts less pressure on them. If we reduce the air mass, the effect is similar, less air molecules to interact with the walls and exert pressure.

This is something which keeps cropping up around the forum lately, where there is this idea that "faster moving air has less pressure" or something...

L. J. Clancy put it most succinctly imo:

"To distinguish it from the total and dynamic pressures, the actual pressure of the fluid, which is associated not with its motion but with its state, is often referred to as the static pressure, but where the term pressure alone is used it refers to this static pressure."

Total Pressure = Static Pressure + Dynamic Pressure

Or another (albeit simplistic) way to look at it...

Total Energy of Fluid = Temperature Energy of Fluid + Movement Energy of Fluid

Bernoulli's equation only holds for air travelling along a single streamline; something often overlooked. What that means is that along that streamline, energy flows between static (static pressure) and dynamic (dynamic pressure) states, but their sum is always constant (total pressure). The dynamic pressure term is just something that represents the decrease in the static pressure due to the change in velocity of the fluid. If you were to stagnate that dynamic pressure, then it would revert back to being just plain old static pressure to ensure the constant total pressure summation.

Fast moving air isn't just "low pressure" on it's own -- there's more going on -- it just has a portion of it's static pressure "converted" to dynamic pressure. The faster the air, the larger that amount of conversion is. Less bouncing on walls doesn't mean less pressure. Slower moving molecules denotes less average kinetic energy of the particles, which in turn, denotes a lower temperature of the air.

godlameroso wrote: ↑12 Apr 2022, 22:50

vorticism wrote: ↑12 Apr 2022, 22:40

godlameroso wrote: ↑12 Apr 2022, 21:58

Air has no mass then?

Lift does not increase the mass of the wing. Barn drafts would have a negligible effect on the weight of the air inside the barn. There are generally not air pockets of considerable size within wings, even if there were, fluctuations in air mass within them would be negligible as a bouyant lifting force compared to aerodynamic lift.

Lift is a force, the force is generated by air pressure, pressure is a result of mass x acceleration. If air had no mass, there would be no aerodynamic forces, period.

Lift / downforce doesn't increase the "mass" (more specifically, the weight force) of the wing, but as I showed above in my thesis screenshot, it does still act in a similar way, but without the drawbacks of an increase in weight.

Pressure is "mass x acceleration"

divided by a unit of area.

And just to tease a little bit, an object that has no mass can still exert a force on something

Photons of light do this, however, their force derives from momentum transfer that is a function of their wavelength and the planck length. It's kinda a cool fact that you technically weigh more during the daytime than you do at night, since there are more photos transferring their momentum to you when they hit your skin during the day. I guess there's a hack for anyone to try out if they ever want to go on a diet

Ok, I think that covers everything... any questions?