This is probably the same idea of flynfrog (I couldn't understand his post 100%), but couldn't part of the CO2 escape through small holes under the body to create an air support, instead of using wheels? Like the "air-pong" tables?

This would give the car an ultra-low rolling resistance coefficient. I do not know if this implies an excesive waste of "fuel", but for the low weight you mention and the mandatory propulsion system, it could be a winner. If this is feasible, I would suggest for this "hovercar" to have wheels anyway, to "fall on them" once the CO2 pressure goes below the "sustaining" point, in order to use all the remaining gas and, also, to use the inertia the car has when it runs out of fuel. Steering or keeping the car in a straight line would be a hard one to resolve.

About the bearings, I've found nothing can beat the old jewel-bearings for clocks for low drag. They are light, easy to find and easy to reuse. But I guess they would not be useful for wheels, as they are made for vertical loads. Perhaps if you "clamp" the axle between two of them...

At least, if you use the air suspension and the jewel-bearings, the name for the car is clear: "The Ruby Slipper"...

I concur with Flyn's remarks about the drag coefficient being less important. I posted

here a extremely simple worksheet that gives you the approximate energy you spend on inertia, drag and rolling

for F1 cars, if you want to check. Anyway,

here you will find one of the lowest drag coefficients measured in history (0.06!), based in the form of a boxfish. I posted somewhere in the forum another article about this car. I don't know if it will work, but

it has one of the most important engineering characteristics: it is super cool!

On the principle that rolling resistance is more or less constant and drag resistance varies with the square of velocity, I bet the problem is on the rocket-propulsion efficiency, to overcome inertia, as Flyn points out. In this case, you could try to make a proper nozzle. The theory is

here.

The idea is that the impulse you'll get is:

This leads to the idea that the only important parameter in nozzle design is the expansion ratio:

This is true IF THE CHAMBER PRESSURE IS CONSTANT (sorry for yelling). As this is not your case, because as the CO2 is expended you have lower and lower pressure, you could try an aerospike nozzle, like Mikey_s suggests. Rocket engineers use aerospikes only for high altitude rockets, but this is because they keep a constant chamber pressure.

Besides, this is true in theory, but engineering is an entirely different matter: if you have not measured it, you have made no engineering.

Here you have some typical values of form factors, taken from the same source, for different types of nozzles:

Please, take in account, before losing too much time with the aerospike concept, that it works in part because of the supersonic flow effects and the problem of the ambient pressure going from atmospheric to zero, that (I guess) are not problems in your design...

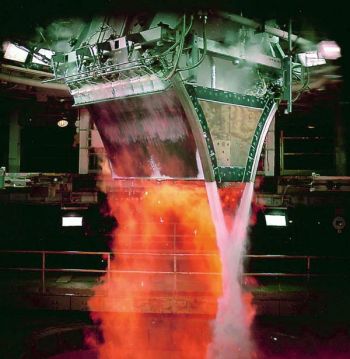

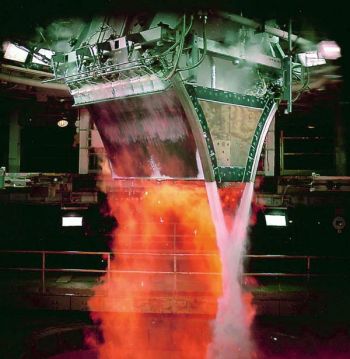

Aerospike nozzle being tested:

Legendary Messerschmit 262, one of the first jet aircrafts (and the first one to be used regularly in combat) showing the spiked bodies on the jet exhaust, used to vary the throat area for maximum efficiency:

So, in essence, you have the inverse problem of rocket engineers: ambient pressure is constant, while chamber pressure decreases all the time down to zero. This gives me another idea: if you use some kind of plug like the one shown for the Me262, you could use a spring under the plug. As the chamber pressure decreases, the spring stretches and the plug moves backwards of the nozzle, diminishing the throat area. Another idea that seems hard to engineer, but it has the merit that I've never heard of a "reversed aero-spike".